Currencies Outlook – US dollar high(er) for longer

Key points

- The US dollar looks set to remain supported by high US yields and a continuation of US’s macro resilience

- Both the euro and sterling are not cheap, with weaker fundamentals and are likely to depreciate

- In a US soft landing scenario, high betas might get a chance to finally shine. The Norwegian krone is particularly cheap

- Japan’s yen might breathe again if rates stop rising, but don’t expect it to steal the show

Fed, not US dollar, peak

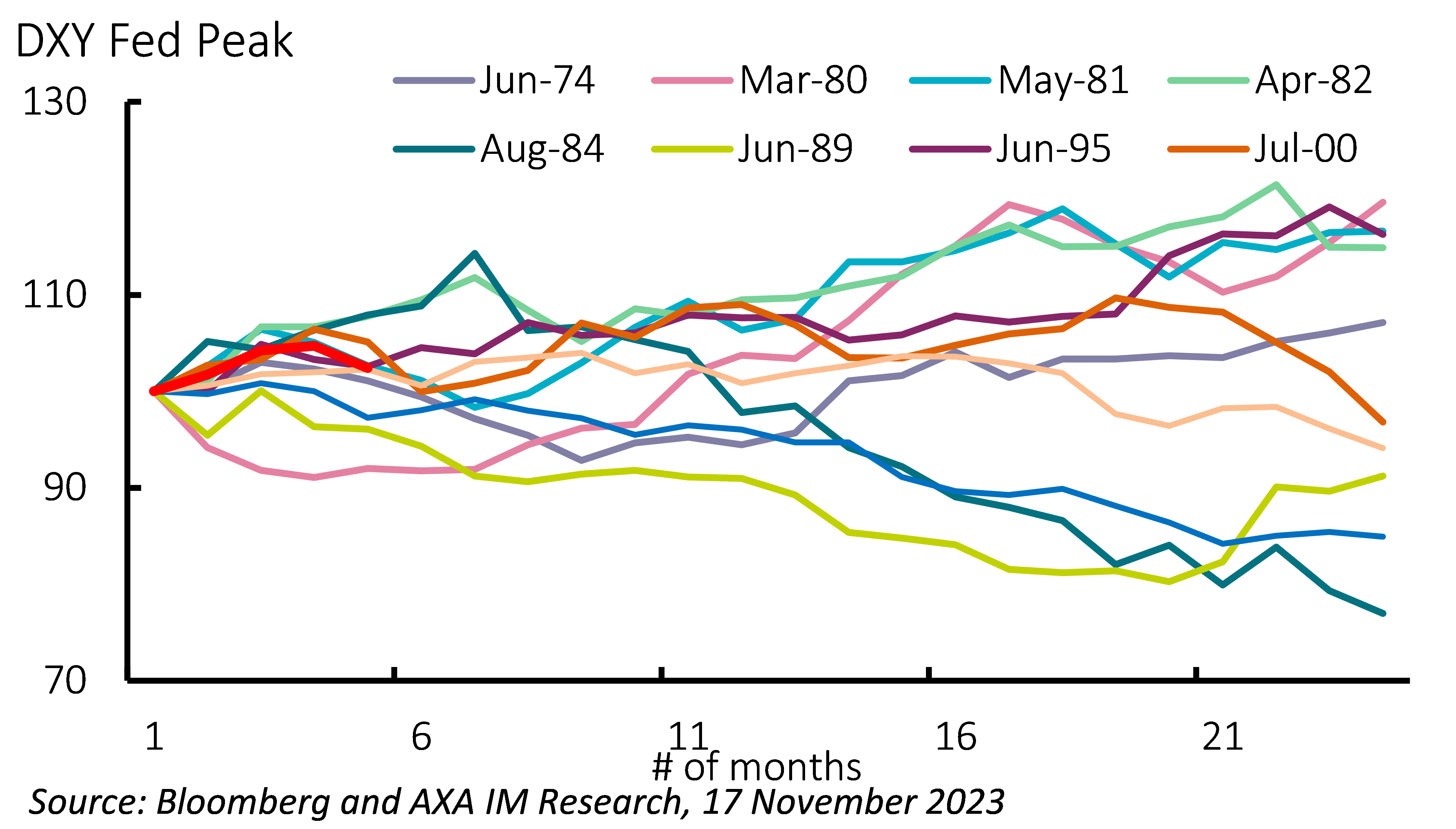

After markets’ multiple attempts to call the Federal Reserve's (Fed) last hike in this policy cycle, it seems we have finally reached it. At its last meeting it left policy unchanged at 5.25%-5.50% and while the Fed is reluctant to say it has peaked, we believe it has. Rising US rates have been a key factor behind the US dollar’s (USD) strength in 2023 but it doesn’t mean it is doomed to fall if rates stop rising. Looking at previous cycles (Exhibit 1), there is no clear evidence to suggest this, particularly looking at the 1970s and early 1980s high inflation periods.

Exhibit 1: Fed peak not necessarily leading to USD weakness

US inflation is softening but not yet back to target, and neither the economy nor labour market have materially decelerated. The transmission of tighter policy seems particularly slow and as long as the market keeps pushing back the perspective of rate cuts, the USD will remain supported.

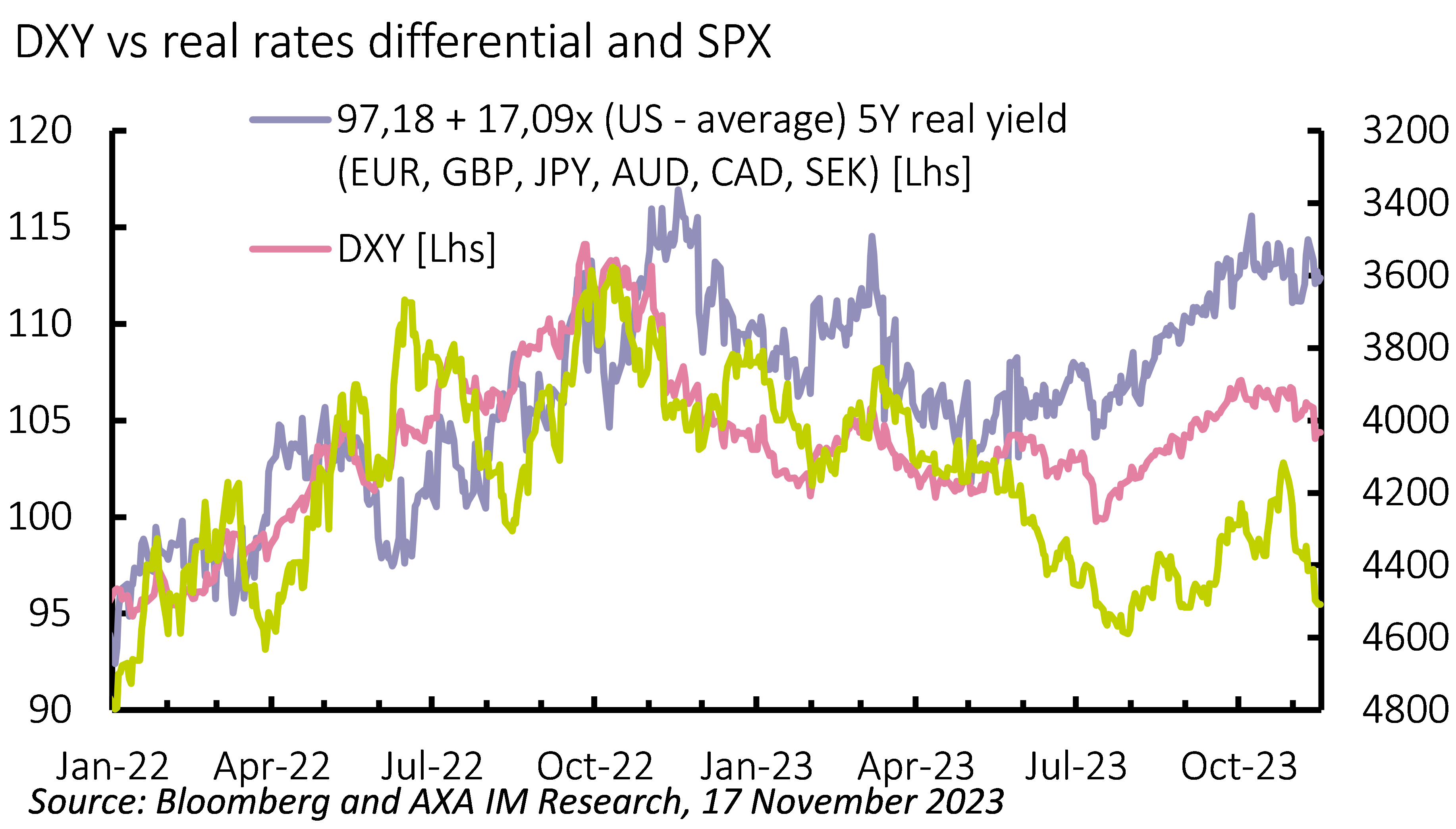

The greenback is undoubtedly not cheap but for good reasons. It has now become the undisputed high yielder within the G10 – even against the renminbi (RMB). Additionally, as mentioned, the US is showing much greater resilience against global monetary policy tightening (Exhibit 2), which supresses the point in the horizon where it might be ousted by foreign yields. Stability in yield differentials might only mean USD stability, not strength. But the market is so far only expecting other central banks to mostly match the Fed’s cut pace, not exceed it.

Exhibit 2: Unrivalled US exceptionalism

Reality check for euro and sterling

The euro (EUR) is firmly in the expensive camp too. When looking at the real effective exchange rate, it has actually appreciated the most amongst the G10 (Exhibit 3). Not only did it depreciate by less than most against the USD but it also endured a much higher PPI-based inflation trend, looking at a seven-year time horizon (both criteria found as the most statistically relevant, focusing on more tradable items).

There are fewer reasons to support such a valuation. The Eurozone economy has slowed more than the US, inflation is falling faster, and European Central Bank (ECB) policy appears more fragile than current Fed pricing, while higher EUR rates would raise further concerns about Italian sovereign debt. Unlike in November 2022, when the prospect of China reopening was boosting global growth forecasts, the potential rebound on this front looks much slower. Indeed, we expect an upcoming growth differential with the US and a renewed focus on ECB balance sheet policy to lead the EUR/USD back towards parity in 2024.

In the post-Brexit world, sterling (GBP) also does not appear to be particularly cheap, although less expensive than EUR. The UK economy has also broadly stagnated over the past 18 months, with the prospect of further weakness ahead. Transmission of Bank of England (BoE) policy tightening is typically faster – the labour market appears to have turned and potential interest rate cuts seem underestimated, relative to other central banks. GBP/USD should also adjust lower.

NOK’ed out but getting up off the canvas

High beta currencies failed to strengthen materially in this cycle and appear – on average – rather cheap. This might in part be explained by their incapacity this time to deliver a higher yield than the dollar. This also might in turn reduce the potential drawdown under risk, from a move towards lower yields.

USD rates have been a dominant driver in 2023 and left little room for high beta currencies with unexceptional yield momentum. Risk sentiment needs to take the driving seat again for those to rise. This might be the turn the USD has recently taken with rising confidence in a soft landing (Exhibit 4).

Australia, New Zealand, Sweden and Norway all have highly indebted households with short-maturity mortgage resets which could lead their economies to decelerate faster. But if a global soft landing emerges Norway’s krone (NOK) has more potential for a comeback from a currently very cheap valuation. Domestic growth looks more resilient than in Sweden. Both the Australian dollar (AUD) and New Zealand dollar (NZD) are also currently impacted by their ties to Chinese growth, although the domestic housing markets appear in better shape.

Exhibit 3: EUR not cheap, but NOK and JPY are

Japan’s yen: Rate differential is yesterday’s enemy

The yen’s (JPY) sharp undervaluation is fully explained by the divergence between Fed and Bank of Japan (BoJ) policy. The USD/JPY has been faithfully tracking the US-Japan 10-year rate differential over the last two years, while the BoJ maintained its yield curve control (and negative rates as the Fed hiked by 525bps, with echoes from other central banks impacting all JPY crosses.

Now the Fed has probably peaked, the next move is for (eventually) lower rates, which should take pressure off the yen and allow some rebound. But as discussed, US rates may remain high for longer – any bounce might be slow and limited, in particular against the USD. And with a 6% adverse carry, there is no incentive to position too early. We do expect the BoJ to shift away from accommodative policies, albeit cautiously, waiting for confirmation on wage growth, while inflation is decelerating globally and not rising locally.

Exhibit 4: USD torn between Rates and Risk drivers

Renminbi’s golden parachute

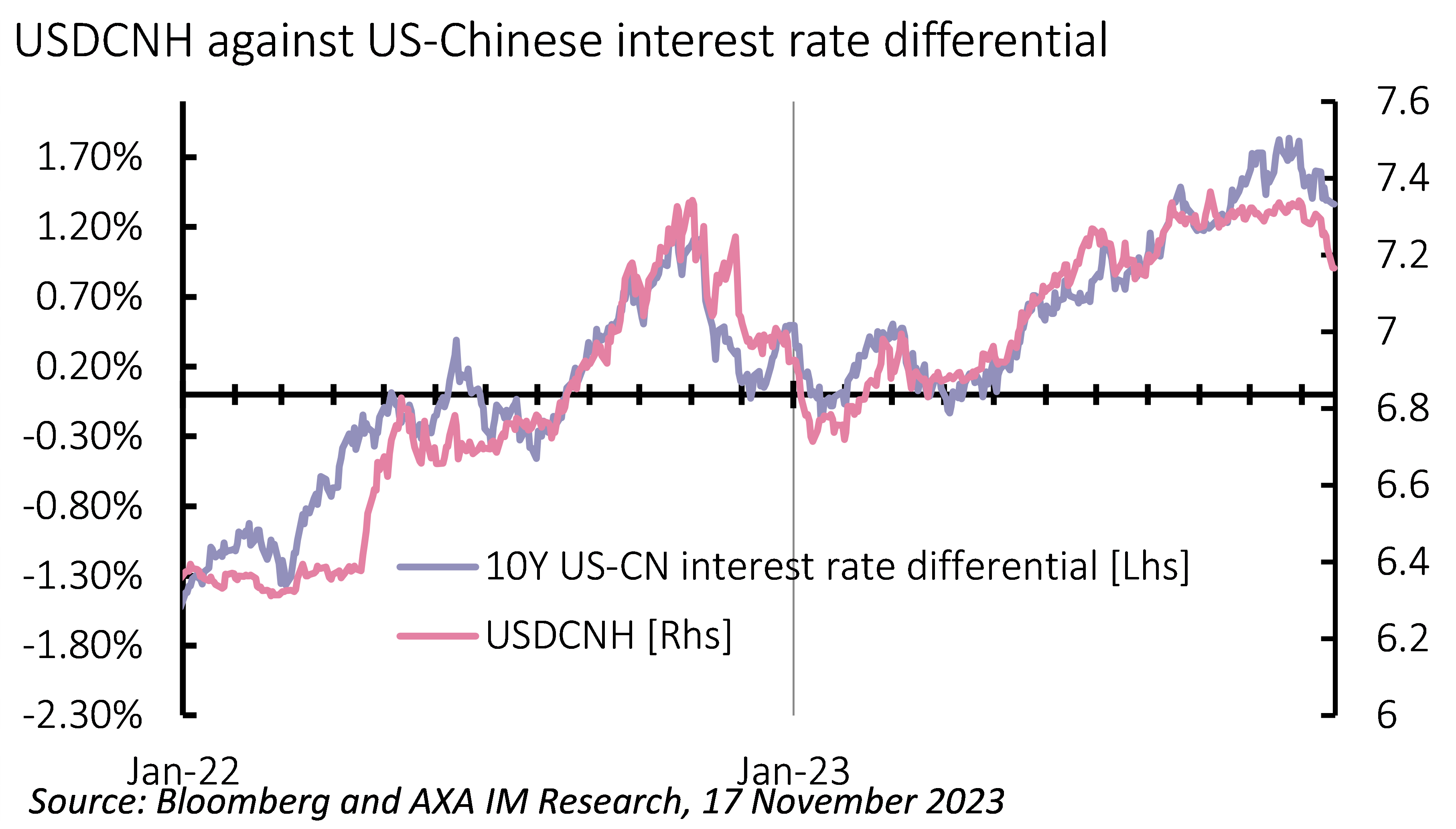

As with the JPY, policy divergence is the main reason for RMB weakness over the past two years - and there is also a very close link between the 10-year rate differentials and USD/CNH – offshore renminbi (Exhibit 5). The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) is maintaining lower domestic rates to manage the transition and revive its economy. China’s growth failed to rebound as quickly as expected in 2023 after reopening and fiscal support remained limited to avoid reigniting excess leverage until the second half of 2023. Investment flows should remain muted with such low rates and higher geopolitical tensions. The trade balance has also yet to deflate from pandemic-era levels, as global demand decelerates, and China imports rise again.

The PBoC is trying to resist those weakening pressures on RMB by maintaining lower USD/CNY fixing and withdrawing liquidity. This policy might take a heavy toll on foreign exchange reserves if USD rates remain high for longer.

Exhibit 5: PBoC action causing USD/CNH to diverge from rates

Disclaimer

This document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment research or financial analysis relating to transactions in financial instruments as per MIF Directive (2014/65/EU), nor does it constitute on the part of AXA Investment Managers or its affiliated companies an offer to buy or sell any investments, products or services, and should not be considered as solicitation or investment, legal or tax advice, a recommendation for an investment strategy or a personalized recommendation to buy or sell securities.

It has been established on the basis of data, projections, forecasts, anticipations and hypothesis which are subjective. Its analysis and conclusions are the expression of an opinion, based on available data at a specific date.

All information in this document is established on data made public by official providers of economic and market statistics. AXA Investment Managers disclaims any and all liability relating to a decision based on or for reliance on this document. All exhibits included in this document, unless stated otherwise, are as of the publication date of this document.

Furthermore, due to the subjective nature of these opinions and analysis, these data, projections, forecasts, anticipations, hypothesis, etc. are not necessary used or followed by AXA IM’s portfolio management teams or its affiliates, who may act based on their own opinions. Any reproduction of this information, in whole or in part is, unless otherwise authorised by AXA IM, prohibited.

Neither MSCI nor any other party involved in or related to compiling, computing or creating the MSCI data makes any express or implied warranties or representations with respect to such data (or the results to be obtained by the use thereof), and all such parties hereby expressly disclaim all warranties of originality, accuracy, completeness, merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose with respect to any of such data. Without limiting any of the foregoing, in no event shall MSCI, any of its affiliates or any third party involved in or related to compiling, computing or creating the data have any liability for any direct, indirect, special, punitive, consequential or any other damages (including lost profits) even if notified of the possibility of such damages. No further distribution or dissemination of the MSCI data is permitted without MSCI’s express written consent.

AXA IM and BNPP AM are progressively merging and streamlining our legal entities to create a unified structure

AXA Investment Managers joined BNP Paribas Group in July 2025. Following the merger of AXA Investment Managers Paris and BNP PARIBAS ASSET MANAGEMENT Europe and their respective holding companies on December 31, 2025, the combined company now operates under the BNP PARIBAS ASSET MANAGEMENT Europe name.